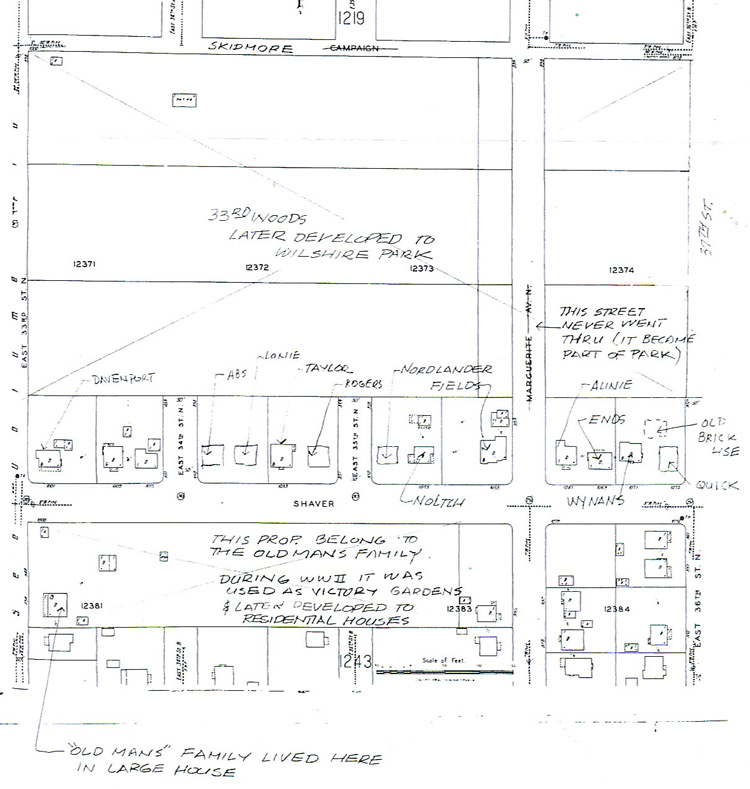

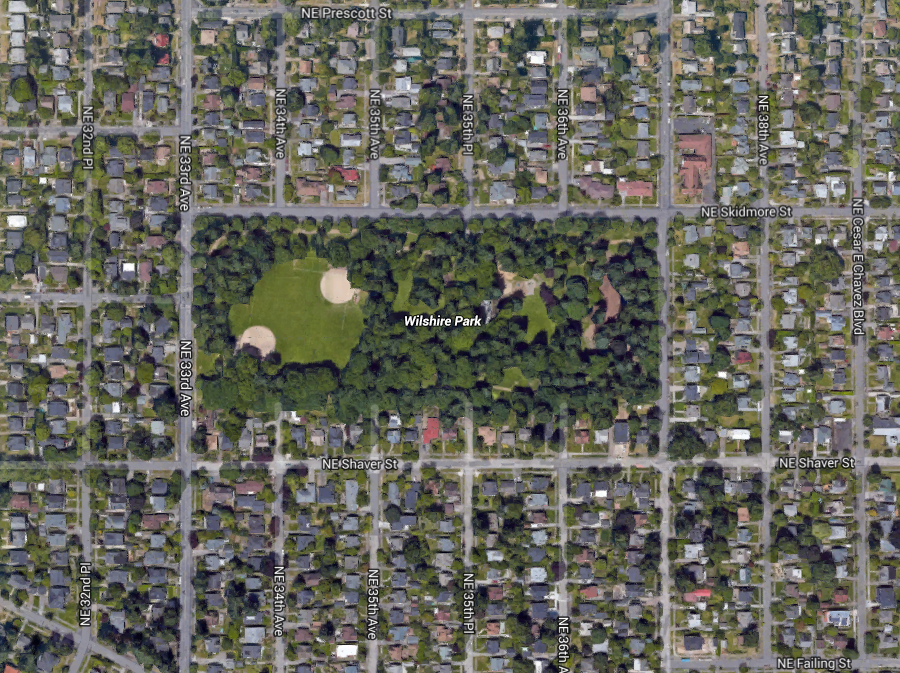

We take Wilshire Park as a given in our lives today, but a look back in time shows it has narrowly escaped several possible fates, including being developed as campground in the 1920’s and later into a housing development. The park traces its history back to an investment made by one of Portland’s wealthy early residents, Jacob Kamm (1823-1912), who made his fortunes in the steam navigation business. Kamm also dabbled in real estate investment and had strategically purchased parcels downtown and at the edges of Portland, including the 15 acres of woods just north of the Alameda Ridge off the old county road (today’s NE 33rd Avenue), which he platted as the Spring Valley addition in 1882. When Kamm died in 1912, the tract had been untouched, and his estate was valued at $4 million. Sorting out the estate took years and was frequently in the press.

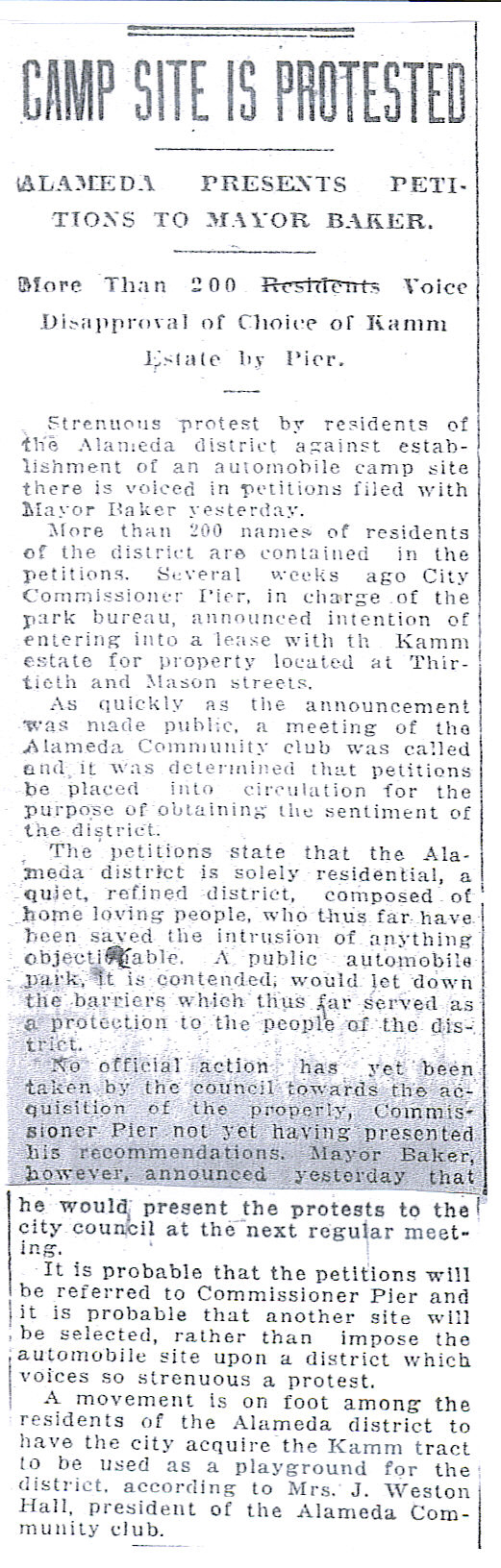

An effort to turn the park into a KOA-style automobile campground in 1920 was cancelled with prejudice by vociferous neighbors who were worried about its impact on property values and didn’t like the notion of a non-residential and transient-based activity being so close to their homes. After that fight, which involved petitions, community meetings and a high level of consternation with city government, the fate of the 15 acres rested for a few years. For the full story on the battle over the land, head over to the Alameda History Blog.

The topic goes quiet then, resurfacing six years later in September 1926 when the city mentioned the property as a possible future public park. It would take another seven years until 1933—with the property connected to the still unsettled Kamm estate—that the city would seriously consider the idea. The early 1920s were a major boom period for the construction of homes in this area. All around the 15 acres, new subdivisions (and lots of kids) were springing up. Kids from these neighborhoods were already using the wooded area as their playground, with a maze of improvised trails, forts and other secret places nestled into the thick brush and trees.

The Wilshire Addition Community Club—a kind-of early neighborhood association and social club—was the first to call for acquisition and development of the park, submitting a proposal in September 1926 for the city to float a bond measure to fund the work. But Portland Parks Commissioner C.P. Keyser felt the chances of a voter-passed measure were too slim because not enough planning and survey work had been completed, so the effort stalled. Left on their own after the city chose not to take up the cause, neighbors began direct negotiations with the Kamm estate. By 1933, an agreement had been reached that allowed the property to be used as a park—still owned by the Kamm family—as long as the planning and development work was funded and conducted by neighborhood residents. In a Monday morning, March 27, 1933 news story, The Oregonian reported the following:

Improvement of a 15-acre tract of land has been started by residents of the Wilshire District to convert the site into a park. The land has been made available by the Kamm estate with the proviso that improvement expenses be assumed by persons living in the neighborhood. Volunteer workers gathered at the tract Saturday and yesterday and cut away underbrush and cleaned the land for further improvements.

Thanks to work parties like this, and continued use by neighborhood kids, community interest continued to build in the mid-1930s—with the property still in the hands of the Kamm estate—until a proposal was made in the fall of 1937 to have the city purchase the property with a localized bond measure. Backers of the proposal knew that time was running out to keep the park as a park, and told The Oregonian in December of 1937 that “this is the last chance to get it. Contractors want to take over the property to build homes.” They also continued to make the case that the nearest proper park was too far away for children to use.

The 15-acres was still a glorified brush patch. Working with neighbors, the city proposed assessing the agreed purchase price of $28,500 across 3,000 homes within the surrounding vicinity, less than $10 per household. This did not go over well with some, and a firestorm of letters to the editor and complaints to City Hall boiled over. More than 30 percent of the 3,000 homeowners signed petitions opposing the fee, though not all were against the park acquisition itself, if the city could find a way to spread the cost city-wide. In 1937, Portland was in the grips of a recession that followed the Depression, and joblessness and foreclosures were headline news on a daily basis. Creating a park was not a high priority. One letter writer, local resident Spencer Akers, put it this way:

The controversy over the proposed Kamm park seems to be fanned to a red heat. Where is the justice in a comparatively few individuals being obliged to shoulder the purchase price, especially since the depression has reinforced its destruction siege by the surprise attack of the ruthless ‘recession?’ If the city is too poor to purchase the property than why in the name of common sense should we, who happen to live in the immediate vicinity, be judged as financially able to raise the whole purchase price? I know of several families in this district who are actually in need, and a bombshell of this nature would play havoc with their tottering defenses.

An editorial from The Oregonian made an eloquent case otherwise:

If the Kamm tract were certain to remain available for a park for a number of years, and the majority of the residents of the district desired that buying of it be deferred, there could be no sound objection to such a course. It is likely, however, that the tract soon will be developed for residential purposes if it is not taken over for a neighborhood park. The national cry for more housing and the probability of advantageous federal financing for building make that seem inevitable, if the city does not act now. The price is reasonable, probably lower than it will ever be again. No other property is to be had for the purpose. The proposed assessment [of $8.60 for a 50 x 100 foot lot] would be unlikely to be a hardship on anyone; the return of value to the property owners in the district would be obvious.

But forward-looking arguments did not prevail, and after all the fuss, the city dropped the proposal. Meanwhile, kids kept using the 15 acres, brush continued to grow, crimes were reported being committed in the woods, and developers sought to purchase and build on the property. The story goes quiet again, until a brief headline in the April 10, 1940 issue of The Oregonian: “City Acquires Kamm Tract.” The short, page 4 story reports only that the City Council took the action by emergency ordinance and was acquiring the land from the estate at a cost of $28,500, financed with a two year loan from the First National Bank that would be paid off from city funds. Perhaps a development proposal led to the tipping point and the

emergency action…that part of the story is untold. The public purchase of the property brought an important chapter to a close, and secured the land for the future.

However, almost as if the neighborhood needed something more to fight about, controversy boiled again in February 1941 about naming the newly acquired parcel, with some wanting to call it Jacob Kamm Park, which stemmed from a proposal made by the Sons and Daughters of Pioneers. The majority of surrounding neighbors lined up behind a proposal to call it Wilshire Park. After several stormy meetings on the topic, City Council agreed with the neighbors and adopted Wilshire Park as the official name.

By 1950, the city had cut and removed much of the underbrush, constructed the ball diamonds still in place today, and even built a playground, which featured among other things, old Fire Engine Number 2, a 1918 model that was finally decommissioned from service at the SW 3rd and Glisan fire house.

Many other memories remain about the park, including the family that lived in a home at the far southeast corner of the woods around the turn of the last century; Christmas trees cut in the 1920s and 1930s from the “33rd Street Woods;” the World War 2 “victory gardens” planted along the park’s southern edge; the jackstrawed piles of trees and branches left over from the Columbus Day storm of 1962; the generations of baseball players, soccer players, runners and dog walkers who have loved this place.

For more neighborhood history, photos, maps and memories of Wilshire Park and the surrounding neighborhoods, visit Doug’s blog at http://www.alamedahistory.org.